In early October 2018…

about 160 migrants gathered in the city of San Pedro Sula, Honduras. The plan was to spend the next two months walking to the United States, in hopes of seeking refuge from a country suffering from epidemic levels of violence, poverty, and political oppression. Thousands of migrants have made the trek before, and this wasn’t even the first migrant caravan to reach the U.S. - Mexico border. But this caravan was different.

Within a few days, several hundred migrants had joined. As they crossed central Guatemala a week later, the caravan was over 5,000 strong. Once in Mexico, military barricades repeatedly tried to dissuade migrants to return home and abandon their journey. Although the caravan splintered into multiple groups, most migrants continued on towards the San Ysidro port of entry in Tijuana.

By early-November, U.S. media was in a full-fledged, 24-hour news frenzy covering every move by the migrant caravan. As the caravan neared, the Trump administration deployed U.S. military personnel as an excessive show of force, while simultaneously reducing the number of USCIS agents needed to process asylum claims. This ensuing media circus got me thinking about the asylum application process and just like a standard visa application, a passport photo is required. But how would migrants, who gave up everything on a hope and a prayer of getting into the U.S, provide a passport photo?

Polaroid launched their Miniportrait series of cameras in 1971, providing a camera that could deliver consistent & reliable passport imagery. Consistency is something we often take for granted after two decades of dominance by digital camera, but staring in the late-19th century immigration laws seized on rapidly improving photographic technology to require all immigrants arriving in the U.S. to provide a passport photo. Newly arrived immigrants were routinely denied entry to the U.S. due to irregularities in the photographic process. Although negative film greatly improved passport photo consistency over the wet plate process used in the late-19th and early 20th centuries, Polaroid made passport photos far more consistent & inexpensive.

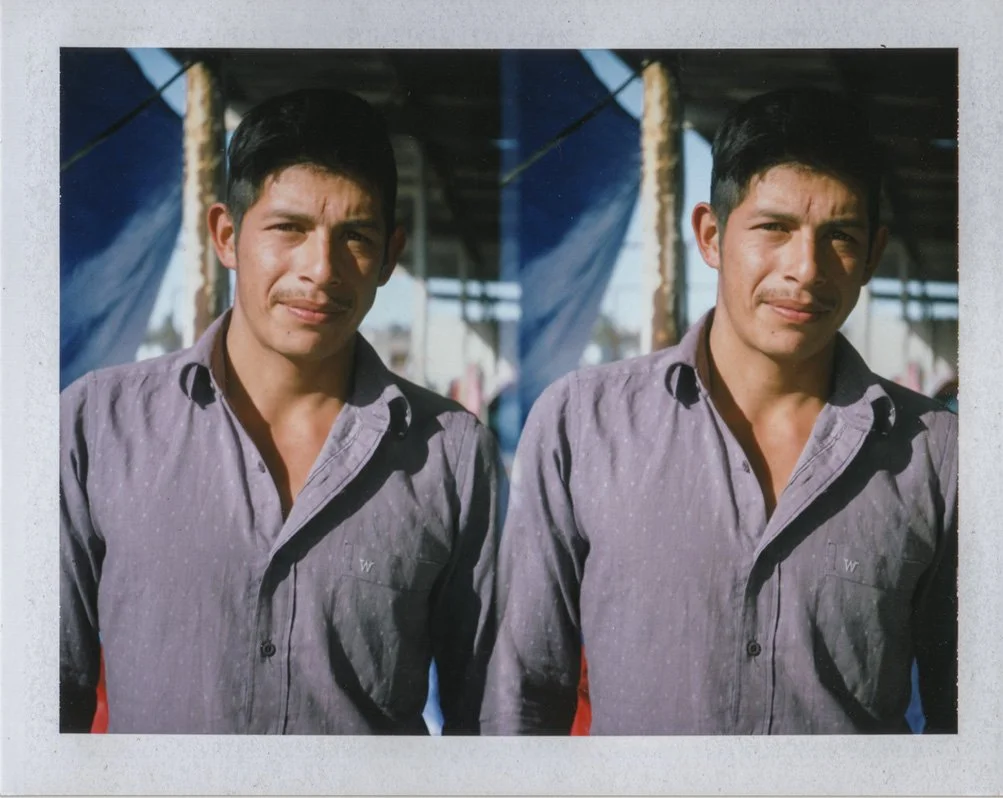

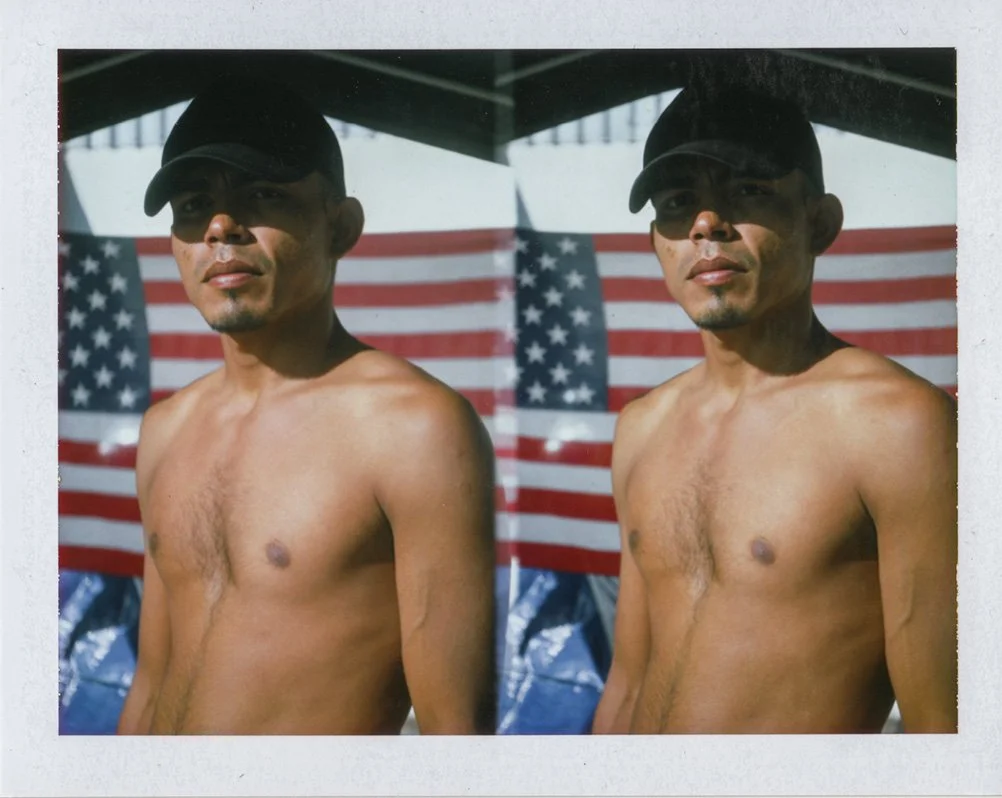

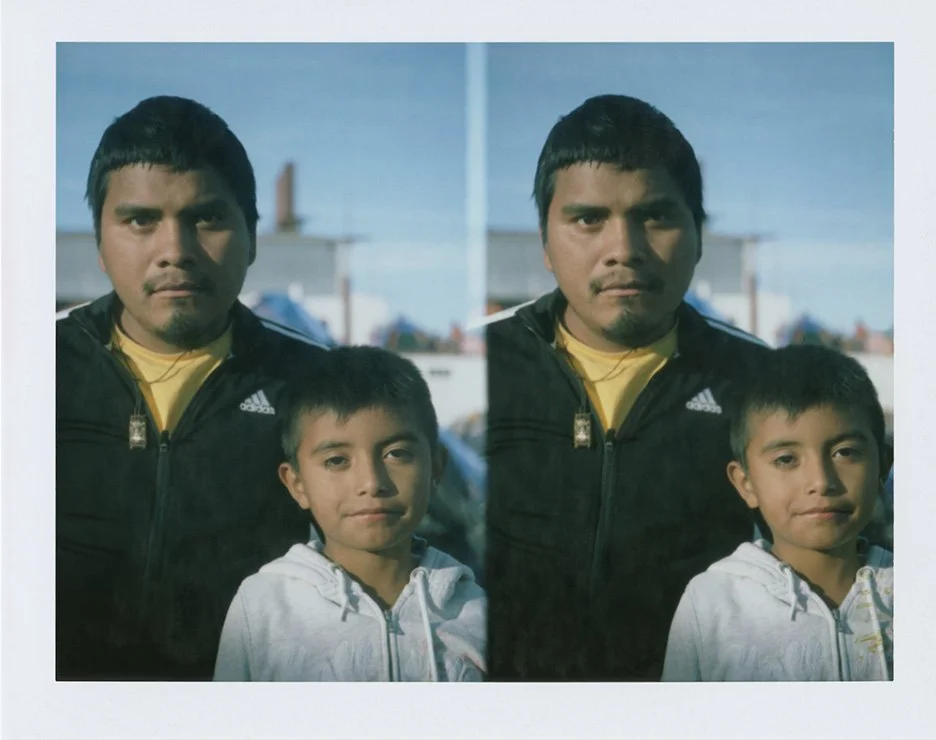

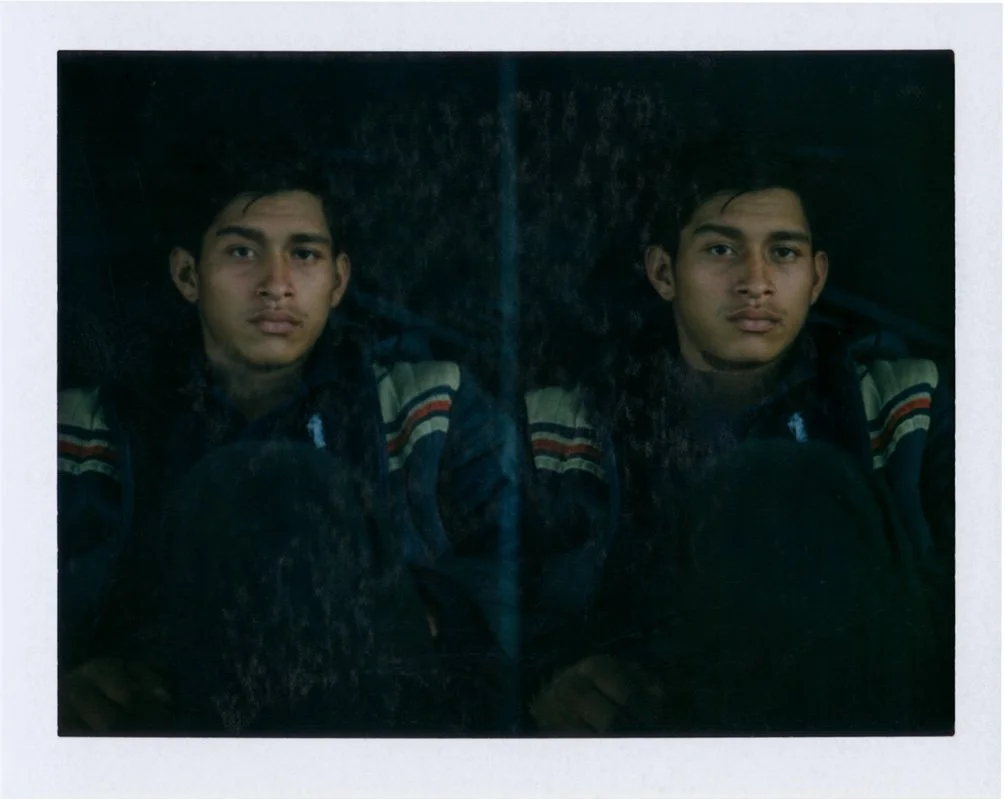

Fortunately, I own one of these cameras, specifically the Polaroid Miniportrait model 203. The camera uses two side-by-side lenses that fire simultaneously, producing two near-identical images, a requirement for the visa process. For film, the camera uses a 4x5 peel-apart film, originally manufactured by Polaroid but later released by Fuji. When Fuji decided to discontinue their peel apart film in early 2016, I bought about 12 packs of film with no project in mind, but with hopes of using the camera for something cool, one day.

In November 2018, with the US media in a full on hysteria, I got to thinking about the asylum process and all it entails. In addition to a lengthy application process and an intimidating interview with US Customs and Border Enforcement, asylum seekers must provide a visa photo, using the same perimeters as my Polaroid Passport Camera. Since most migrants have sold off all their belongings, providing a valid visa photo could make or break one’s journey into to the US. After realizing this, I started planning by visit to the migrant camp once they arrived in Tijuana.

We arrived in Tijuana a day after the camp was moved from Zona Norte to about an hour away in the Torres de Matamoros neighborhood east of the city. The camp was frantic, volunteers did their best handing out supplies while others provided pro-bono legal assistance.

Our plan was simple: we would shoot two photos of each migrant we spoke with. One Polaroid was shot in a standard visa format, while another Polaroid was shot throughout the camp and used here. Some migrants chose to hold onto the image for themselves, others chose to mail their photo back home to Honduras, and some chose to use their photo for the lengthy asylum process. What was important to me was that, this photo was theirs. Most migrants in the camp sold every belonging they owned just on a hope and a whim they’d get into the United States. Throughout their journey, coyotes, shopkeepers, and journalists, among others, all wanted something from the migrants. Some wanted a few pesos, others wanted stories, and some wanted their lives. By providing a photograph, migrants were allowed to choose how they wanted to use their photograph, whether it was a keepsake, a piece of the application process, or a memento to send family back home.

![Alexander Cave [dot] com](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/635c6cf799a6ce163eb3b23f/f0616c43-c80f-4482-a25e-797ea914f913/logo03.png?format=1500w)